Interfaith Bridges From Penn’s Philadelphia to Sheikh’s Sulaymaniyah by Danyar M. Ali

By Danyar M. Ali

My visit to Philadelphia as a young Kurdish law student representing Iraq in an American exchange program opened my eyes to phenomenal parallels between two visionaries, separated by centuries and continents. As I made my way along the path of William Penn’s “City of Brotherly Love,” however, I began to feel Kak Ahmad Sheikh of Sulaymaniyah reaching across cultures with some surprises. The religious pluralism that Kak Ahmad inspired in Kurdistan is as far ahead — and behind — us as that of Penn’s Quakers.

Exploring a range of houses of worship, I was exposed to the spiritual tapestry of Philadelphia. At the stunning Al-Aqsa Islamic Society, the known call to prayer filled halls lined with intricate Islamic calligraphy, yet another familiar comfort miles away from home. A few blocks away, the historic Rodeph Shalom Synagogue was a monument to Philadelphia’s Jewish heritage, its Byzantine-Moorish architecture embodying the cultural synthesis that has always been at the heart of the city.

What most really resonated with me was that these different faiths were not just existing side by side, but in real harmony — a living testament to William Penn’s radical 17th-century vision. Penn, a Quaker who had been persecuted for his beliefs in England, established Pennsylvania as a “Holy Experiment,” a place where people of all faiths could worship freely. This was radical at a time when religious tolerance was simply unknown, and persecution the invariable practice.

While sitting in silent worship at the historic Arch Street Meeting House, where Quakers have been meeting for centuries, I couldn’t help but imagine Kak Ahmad Sheikh doing a similar work in Sulaymaniyah. Sheikh Ahmad, like Penn, knew that authentic religious liberty involved not mere tolerance, but proactive regard and defense for every faith. With its array of other groups, such as Yazidis, he worked to bring together Muslims, Christians, Jews and Yazidis in much the same way that Penn had done amongst the different denominations of Christianity, Judaism and Native American spiritualities of colonial Pennsylvania.

It’s striking how similar these two figures are. Both lived during periods of intense religious strife, but opted to swim against the political currents of their times. Penn founded a colony in which no man should face persecution for his beliefs; sheikh Ahmad strove to heal the sectarian pain of post-conflict Kurdistan. Both men knew that religious freedom was not merely an individual right of conscience but a pillar of peaceful society.

What is even more extraordinary about their accomplishments is how they embraced religious harmony not as a dilution of their own faith but as a manifestation of it. Penn was a Quaker, and his religious views led him to see the light of God in all people, no matter what their religion. Likewise, Sheikh Ahmad used Islamic principles of respect for the so-called “People of the Book” and human dignity to encourage interfaith dialogue and understanding.

As I walked through Philadelphia’s historic district, I imagined how Penn’s vision had borne fruit across generations. Churches, synagogues, mosques, and meeting houses stand as neighbors, their different congregations mingling each day in the marketplace, schools and public spaces. It recalled the work Sheikh Ahmad was doing in bringing interfaith dialogue into the open by forming common spaces for interfaith dialogue in Sulaymaniyah, where the leaders of all the different faiths continued get together on a regular basis to discuss common challenges as well as celebrate their common humanity.

Each of the churches I visited — the Swedish Lutheran Church, the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, the various historic houses of worship — told a story of how a given community found its home in Penn’s grand social experiment. Their activities and vitality continue to speak to the enduring success of his vision, much like the expanding interfaith initiatives in Kurdistan are grounded in the work of Sheikh Ahmad.

As a law student, I was especially struck by how each man strove to institutionalize religious freedom in legal systems. Penn's Frame of Government for Pennsylvania afforded never-before-seen safeguards for religious liberty, while Sheikh Ahmad fought for legal protections of religious minorities in modern Kurdistan. It provides a reminder of a world where human dignity and social harmony are the key tenets, and the law remains a mechanism for protection.

But neither man’s vision was purely hypothetical. Penn actively bridged different religious minds and gathered fair treatment for all; Sheikh Ahmad continually interceded to protect threatened religions and to encourage mutual understanding between sects. Those approaches to enacting their dreams hold relevance in the world today, where one of the greatest challenges across many societies is often interreligious contention.

My exchange program coming to an end, I left Philadelphia thankful for the way William Penn’s “Holy Experiment” has played in broad strokes across time and space, resonating on lofty wavelengths that would engender the most unlikely echoes in the work of Kak Ahmad Sheikh in the land of Kurdistan. Their common dedication to religious toleration and living together serves as an invaluable template for tackling modern-day issues involving plurality and religious strife.

For both Philadelphia and Sulaymaniyah remind us that the courage to imagine a new way of living together, along with practical work of building institutions and relationships, can change societies. These lessons stay with me, taught by two visionaries from distinct times and cultures, arriving at the same conclusions about human dignity and religious freedom. As a law student in the Kurdish region of Iraq, I am both haunted and encouraged by these lessons.

Their legacy serves as a reminder that the task of building bridges between people of differing faiths is never complete, but rather one that is passed down from generation to generation — each one contributing its chapter to this story of human respect and understanding that continues to unfold.

The Significance of Interfaith Dialogue in the Contemporary World by Danyar M. Ali

Authored by SUSI 2023 Alumni Danyar M. Ali

It is fast becoming important in today's world for interfaith dialogues to be appreciated more amidst the religious and cultural diversity characterizing society. This dialogue will not only help people understand one another, but it is also a very important tool in building bridges, and creating peace, and coexistence among such communities. Interfaith dialogue can play a fundamental role in reducing tensions and conflicts, countering extremism, and opening up society towards tolerance.

Another significant result of interfaith dialogue is that it aspires to the complete elimination of misunderstandings and biases between the adherents of various confessions. These usually come from a shortage of knowledge and gaps in personal contact with other people, so very often, this disunity can be solved after the representatives of various confessions sit down together to discuss problems openly and honestly. This helps lessen the fear and suspicion of one another and builds even more trust among religious groups.

Interfaith dialogue leads to increased respect and tolerance in society. As people learn to listen to and understand different perspectives, this will contribute to the development of respect for differences and to a more diverse and open society. Such a dialogue also makes one introspect his belief system yet be open to the thoughts of another. This eventually leads to a vibrant and resourceful society where differences become a form of blessing rather than a point of intimidation.

On the other hand, interfaith dialogues can serve as a looming factor in settling social and political issues. Often, religious factors have to do with problems of global complexity. Inter-religious dialogue thus forms a channel for religious leaders and their believers to find peaceful solutions through their cooperation. This cooperation could also extend to other specified areas, such as the fight against poverty, inequality, and climate change. To this effect, when different religions make a common cause in serving the community, this serves to solve not only the problems at hand but also to reinforce their relations.

Interfaith dialogue also provides avenues for spiritual learning and growth. Each religion carries with it a certain wisdom and unique insights into life and existence. People can learn from the insights of one another through dialogue, thus broadening their horizons. Thus, this will enrich the spiritual and moral life of people and society as a whole. Additionally, interfaith dialogue may help individuals understand their own beliefs more deeply and to think more critically about religious issues.

It is also expected that interfaith dialogue can play a significant role in safeguarding and strengthening religious freedom from the religious oppression and discrimination that still exist in the current world. When religious groups work in unison, they can be stronger to protect the rights of religious minorities against every other form of oppression. This becomes important in bringing about a society where everybody can comfortably practice their beliefs without fear of oppression or discrimination.

Interfaith dialogue also proves to be very important in education. We can teach young people how to view differences and comprehend religious diversity through curricula and joint activities. It is an influence on the new generation in regard to opening up and being more open-minded towards religious or cultural differences. The less children and youngsters are introduced to the existence of different religions, the more they will create a society where differences are a source of fear and hostility rather than a source that enriches social and cultural life.

The other positive aspect of interfaith dialogue is that this dialogue can challenge extremism and terrorism. Religious leaders can, through dialogue, stand up together against any extreme interpretation of religion and disseminate a message of peace and tolerance. This is important in saving the youth from the clutches of extremist ideologies. Sending back to society a signal that different religions come together to raise their voices against violence and terrorism gives a powerful message to the groups who use religion for such violent purposes.

In this way, interfaith dialogue may also serve as a means of preserving cultural and religious heritage. The cooperation and mutual understanding may provide a way for the different religious groups to help each other in the preservation of sacred sites, traditions, and values that are deemed important to be kept in the culture. This goes a long way toward preserving some semblance of cultural diversity in the world and preventing the loss of historic sites and ancient traditions. Also, through dialogue, different religions can learn how to respect each other's sacred sites and work together to protect them.

Finally, interfaith dialogue brings human commonality into development. Irrespective of religious differences, we are all ultimately human, sharing the same basic needs and aspirations. Real dialogue lets us understand this human commonality and builds much better relations based on that. Something shared in common can become a platform on which to cooperate and come together against challenges that face all of humanity, such as poverty, disease, and climate change.

Interfaith dialogue also can play an important role in maintaining world peace. In a world where conflicts and wars are very often related to religious factors, interfaith dialogue can become an important tool for solution of conflicts and the search for peaceful solutions. When religious leaders and believers learn to sit together and discuss, it may become an example for politicians and decision-makers on how one can resolve differences in a peaceful manner.

Yet, interfaith dialogue is not easy-it is fraught with its own barriers. Deep differences in beliefs and traditions, a history of conflict and hostility, and the fear of losing one's unique identity stand as deterrents to effective dialogue. Some individuals and groups also harbor fears that this dialogue might make their convictions weak or that compromise on basic principles regarding their religion may have to be made.

It is, therefore, of essence to conduct interfaith dialogue in a proper and sensitive way. Participants should regard the differences of others with respect and try to achieve commonalities without the intention of convincing others about one's beliefs. A very essential aspect is that this interfaith dialogue should not remain restricted to religious heads; it reaches people at the grassroots level also. For that continuous education and sensitization is required.

We can derive from this that, notwithstanding all the obstacles and barriers, interfaith dialogue is one of the most important tools which can be used in trying to establish a world that is more peaceful and united. It is through dialogue that we understand how to respect differences and find commonality. We can solve together many of the problems that all human beings face. But together, we can foster a society that recognizes that diversity in religion and cultures is an asset, not a source of conflict or division.

That is why all of us-in our personal lives, our communities, our states-should take every possible measure to encourage and give support for interfaith dialogue. It is by encouraging and giving support to the people and organizations who work in this area of expertise. It is necessary that the values of tolerance and respect for differences be emphasised, taught, and spread through our education systems and the media. Only then will we be able to head toward a world where peace and coexistence will have first place over fear and hostility.

Interfaith dialogue is not, lastly, a religious but a human issue and one concerning the fate of all of us. It is the way to greater understanding, closer cooperation, and peace in this world. Let us all join this process and take part in building a good future for all humankind.

A SUSI Reflection By Samaa Hossam (Sky)

The journey of SUSI 2023 began as a mere adventure into a new land, but it quickly evolved into a soul-enriching exploration of five different countries that the participants represent in the program. The friendships that blossomed amidst our diverse backgrounds mirrored the very essence of our theme. Bonds forged through shared laughter, late-night conversations, and mutual respect transcended our differences and became a testament to the possibility of peaceful coexistence. Although we are separated by geography and culture, we found common ground in our quest to understand, accept, and celebrate our differences.

As the program drew to a close, we were heavy with the knowledge that the physical distance between our countries would soon separate us. Yet, our emotions were a mix of sadness and hope, for we carried home the spirit of our collective journey.

The SUSI program wasn't just an educational endeavor; it was a pilgrimage of the heart. And as I look back, I am reminded that we, as a global community, hold the power to bridge divides, foster understanding, and create a world where diversity is not just accepted, but cherished.

Reflection by Samaa Hossam (Sky) - 2023 SUSI Student Leader

Attending Quakers Worship Day by Omar Namiq

On June 25th, my friends Jalal, Danyar, and I made our way to Arch Street to a Quaker church.

Upon entering the church, we were greeted by a lady and a gentleman at the door. We expressed our desire to participate in the worship, and they warmly welcomed us, offering to write our names on stickers and place them on our chests. We gladly accepted and wrote our names, attaching the stickers to our T-shirts.

As I stepped inside, I was immediately struck by the profound silence that filled the room, despite the presence of numerous individuals. I noticed that everyone, including ourselves as newcomers, wore badges with their names written on them. It became apparent that this practice was not exclusive to us, but rather a way of showing respect by addressing individuals by their names when engaging in conversation.

Choosing a seat at the end of the hall, I positioned myself to have a view of all the attendees. Sitting down, I began to observe the people around me and appreciate the beauty of the silence. It was perhaps the first time in my life that I experienced such profound silence in the presence of others.

The room housed a total of 23 people, including the three of us. Among them, nine were female. The majority of attendees were older individuals, but there were also some young people present. As I observed the worship, the predominant feature was silence. There was one young man and woman who remained silent throughout, their eyes closed as if engrossed in a deep communion with their respective gods. I initially believed they were maintaining silence for the entire hour, but then an elderly gentleman slowly stood up and, with a tremor in his voice, shared his contemplation about a passage he had read from Tolstoy. He spoke about how humans never truly die, as only their bodies perish, not their souls. His words captivated the attention of everyone present. After he finished speaking, he sat down, and the silence resumed.

It was during this moment that I realized the significance of Quaker worship. If one feels compelled to share something, they can simply rise and speak, and others will listen attentively. I found this aspect truly beautiful. Here, one has a safe space to voice their thoughts and feelings, knowing they will be heard.

When the clock struck 11:30, a young lady stood up and greeted everyone with a cheerful "Good morning, friends." Suddenly, everyone stood up and reciprocated the greeting, including ourselves, which elicited a lighthearted moment. The young lady then invited anyone who wished to introduce themselves or share something to do so. I raised my hand, stood up, and explained that I come from Kurdistan and that this was my first time attending a Christian church for worship. The entire congregation warmly welcomed me, and my friends, Jalal and Danyar, also took the opportunity to introduce themselves. Subsequently, other individuals stood up, introduced themselves, and one person asked a question, although I couldn't quite hear it clearly.

Following this, we were informed that coffee, tea, and donuts were available if we desired to join the congregation. Without hesitation, we accepted the invitation. While enjoying our donuts, we engaged in conversations with some of the attendees, who proved to be incredibly friendly. They showed genuine interest in Kurdistan, and I found myself immersed in a delightful conversation with them.

Before leaving the church, a lady come and talked with me, she said that we call each other friends, we are “Friends society”. And I asked what about Quakers?, she said “Yes, we Quakers, call each other friends”.

She went on to share with me that they have all agreed upon a set of principles known as SPICES. Intrigued, I asked her to elaborate on what SPICES entails. She explained that it stands for Simplicity, Peace, Integrity, Community, Equality, and Stewardship. Personally, I believe that these principles are fundamental values shared by all religions, although regrettably, people often fail to uphold them.

Seeking further clarification, I asked her what would happen if my inner light led me to a different god than hers. She responded with a lighthearted tone, saying, "Ask three Quakers about God, and you may receive five different answers." We shared a laugh, and she continued by emphasizing that Quakerism grants individuals the freedom to follow their inner light. She expressed that each person's inner light is unique and different from others', and they do not inquire about which god one's inner light guides them towards.

Curiously, I inquired whether a Muslim, or anyone of another religion, could be considered a Quaker. She replied with a jovial tone, "Yes, Hahaha, if they follow their inner light." At that moment, I noticed another young lady who shared with me, "I love the freedom my religion has provided for me."

Eventually, the time came for us to bid farewell. We turned around and said goodbye to everyone before leaving the church. This experience marked my first attendance at a worship outside of the mosque, and it allowed me to witness firsthand how individuals with different religions and beliefs worship their respective gods.

I found solace in the profound silence and felt a genuine connection with the people I encountered.

Reflection by Omar Namiq - 2023 SUSI Student Leader

We The People by Ricky Adityanto

We The People: What’s the meaning of becoming “people” in plural community?

By Ricky Adityanto

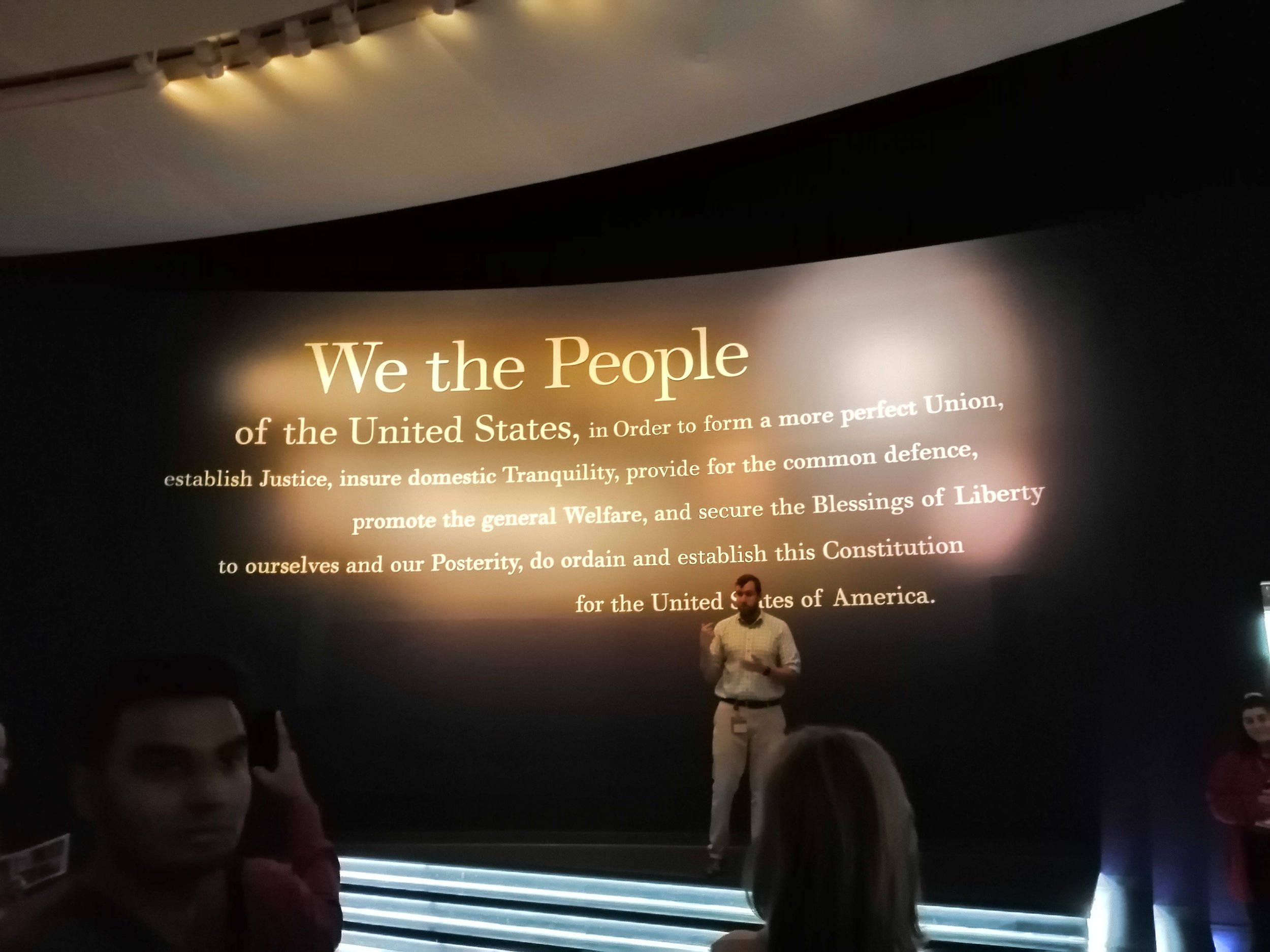

We the People

The first phrase of the US Constitution that struck my mind. Spontaneously, my mind raised a question: “who is this “the people”?”. History showed us again and again that we always had disputes and arguments on who or what can be considered as “our people”, making a thick line that segregates “us” and “others”. But, could you really choose whether we were born as “us” or “others”? What if you were born as “other” in “us” neighborhood?

Do you see the problem here?

Back to the fundamental meaning of “people” and person

Again, we have to learn from history, from people that sacrificed their lives to redefine the definition of “the people”. From Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, to Nelson Mandela. Did they struggle only for the sake of “being black”? I believe the answer is no.

I believe that the deeper meaning of their struggle, their campaign, was because there were someone’s life and dignity at stake. There were men and women at the verge of death because of segregation. There was a human that died from injustice. At the most fundamental level, they did for human life and dignity.

Wouldn’t you feel angry if you are treated unjustly? Wouldn’t you feel angry if “your people” are treated as “others”, as alien and are stripped from your right as a member of a society? Wouldn’t you feel that all those violate your dignity as a human being?

So, you and I, “us” and “others”, we all have life and dignity as human beings. That line between “your people”, “our people”, and “others” in a society is just a skin-deep definition and categorization but at the core of our soul, we are all human beings. We are “the people” of humanity that have life, dignity, and in turn, rights as a member of society.

“The people” is about we as humans that have life and dignity.

So, what’s the meaning of our “skin”?

White, Black, Asian, Native American, etc. are all “the people”. But, does it mean we are the same? What’s the meaning of our uniqueness then?

All our uniqueness together is another part of the definition of “the people”. There’s no one else in this whole world that can replace you due to all your uniqueness, thought, feelings, talents, and your personal experiences. Thus, if you try to be somebody else, the world will lose the “genuine you”.

On a community scale, each community has its own culture, idealism, vision, way of life, and membership that are so unique they can not be replaced by other community. So, being White, Black, Asian, or Native American is not only about “having skin” but is your culture, your way of life, your name, being your unique self, and your community in society. And being happy with it!

Hence, “the people” is also about being your unique self in society and being proud of it!

Participation of “the people”

All these unique communities together build a society. We are part of society. Since society consists of us with our uniqueness, then we have an important part in our society: giving our unique selves.

This is then the meaning of being White, Black, Asian, or Native American as “the people” of society: being all that’s unique from where you come from, and giving all that uniqueness for the betterment of society. We can think of “the people” as a rainbow, where humanity is the raindrop and the sky with us and our personal background as its color. Being “the people” is all about celebrating humanity with its all colors and giving all those colors to the world.

Come to think of it, “the people” really have a beautiful meaning, isn’t it?

A SUSI Summer 2022 Reflection: Ricky Adityanto

What is human?

This was my simple question when I flew to the USA for my SUSI Summer 2022 program. As a multilevel minority in Indonesia (Catholic, Chinese mixed descent, queer) I experienced many discriminations in my life. I tried my best to contribute to society as a good person so people won’t question my identity as a problem anymore just like Gus Dur (the 4th Indonesia’s president) said: “If you are a good person, no one will ask your religion”.

But still, I questioned my identity at that time. Yes, I believe that God created us differently and each one’s unique identity is a hidden gem. But in reality, those differences are often seen as problems. What if I, for once, proudly show my identity without any social pressure? Would I grasp a deeper meaning of being a human?

Who is human?

“We the people”. That part of the preamble of the US Constitution was one of the major points of my reflection. Who are the people? We are all! No matter your religion, skin color, gender, etc. We are all the people. We are all human!

I was really touched when for once I could be proud and accepted for my identity during the SUSI Summer program. And in turn, I was blessed to know my friends’ unique identity in SUSI that I never met before in Indonesia. Unknowingly, I become blessed precisely because of the unique identity that molds me into a unique person. I was there, I met them, had conversations with them, and helped them as a unique color called “me”. No one can replace me and my color.

At that point, I understood that being human is being me with all my identity, and giving that “me” as a whole in my relation with others. And having identity means having struggle. So, I must be open to the others’ and my own struggle in my relation.

Why human?

"If the church stays silent, who will speak for the poor and discriminated?”. This speech I got in Bethel Church, Philadelphia, still gives me goosebumps now and that is also the answer to the next question: why human?

We are all blessed through our unique identity and struggle! Our identity and struggle shape us as a person with our own lessons that we learned from our struggles. And our mission in this world is simply to be truthful to ourselves, to our “color”, learn from the struggle, and share what we’ve learned from the struggle to inspire a better society. Be a unique blessing for others that can’t be replaced.

So, here I am, sharing with you what I’ve learned so far. If I stay silent, who will speak for people who are in the same identity group as me?

How to be human?

I can’t mention one by one all the beautiful quotes I got from all the beautiful-hearted people I met during SUSI. I can say that I met big people with even bigger hearts there. But, one important thing I can say is they showed me how to be human: embrace the identity, and the struggle, and share and care for others.

And they showed how to do it in the simplest way: through friendship. Through friendship, we open to others’ struggles, we try to understand and respect others’ identities, and we learn how to share and care with kindness. We also respect ourselves by staying true to our identity and giving it as a gift to others. And together, we paint this world with our combined colors, creating new colors that we never thought could exist before. This is exactly what dialogue is all about.

A SUSI 2022 Alumni Story: Arshad Khan

"Growing up in a traditional business-oriented joint family in a drought-prone district of Telangana, I have been perceiving what it takes for a multicultural society to exist in the present-day world.

I graduated from St.Mary`s College with BBA. Since the day I moved to Hyderabad for my higher education, I have always been seeking a platform to nurture my idea of multicultural coexistence, and that's where I found Rubaroo NGO based out of the city who is relentlessly working on education and human rights advocacy. A 3-day workshop on interfaith included playful activities on values, perceptions, conflict management, and the social action project we conducted in a women`s degree college in Mahabubnagar has brought me a proper understanding of how to resolve conflicts among smaller groups and avoidance of communal violence.

Over time, Rubaroo NGO nominated a few youth champions of the previous workshop for a US exchange program called SUSI, Study of the U.S. Institutes (SUSIs) for Scholars.

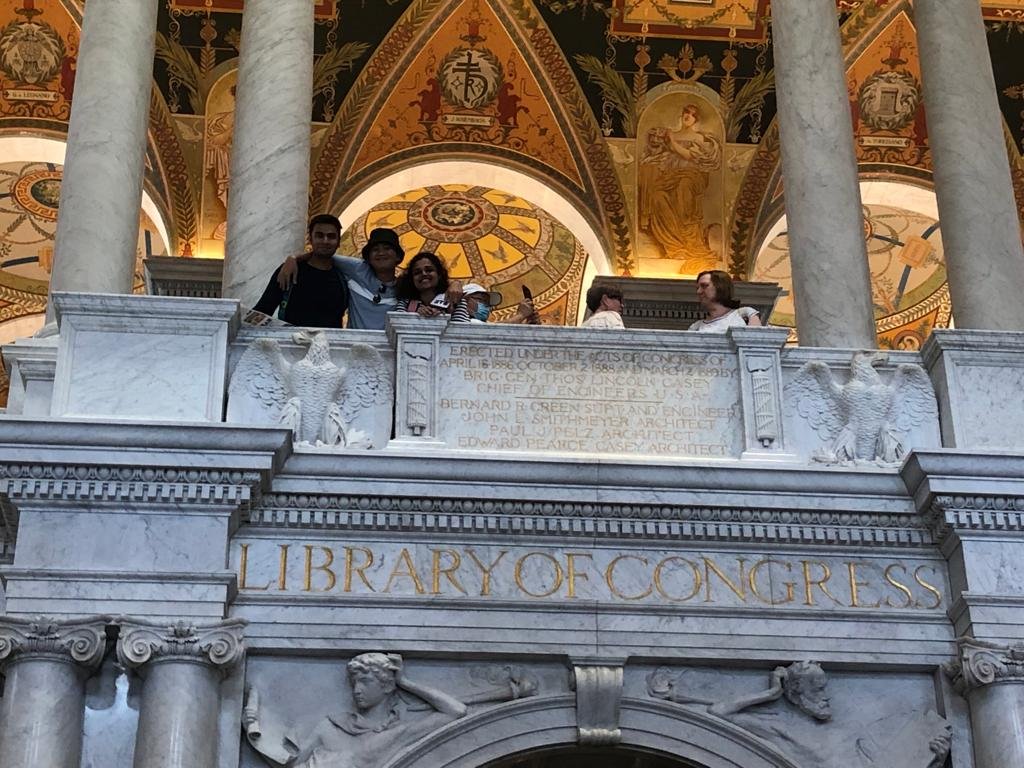

Among them, I was selected for the cohort Religious Freedom and Pluralism. Unfortunately, the pandemic began the year in which we were supposed to fly to the United States for the 6 weeks of the study tour. So we had to go through the sessions virtually for two months and the community action project in further time and then eventually things were getting better. Finally, in Oct 2022, we flew to the United States for a 10-day capstone program on religious freedom and pluralism which included round table meetings on democracy, lectures by Temple university professors on Religious freedom, walking around historical monuments and worship places in Philadelphia city, an interfaith community center in Baltimore and the Washington DC.

My whole journey at SUSI consisted of challenges and surprises but I must say it's truly a remarkable and worthwhile experience on the whole as meeting new people beyond the border with similar thought processes has truly nurtured my idea of multi-cultural coexistence."

- Arshad Khan, SUSI Alumni 2021/2022

A SUSI 2018 Alumni Story: Amira AbdelTawab

“Be the change you want to see in the world."

- Mahatma Gandhi

Although the chaos I have been through now in all aspects of my life, I still remember when I was 16 years old, I was dreaming of having a good future and becoming a successful young woman, and changing the world when I grew up. It wouldn’t happen until I traveled to study abroad not in any country, but only in the United States of America.

I was obsessed with traveling to the USA, it was my biggest dream since my childhood to be in the wonderland living the American dream, so during my university year, I studied hard and participated in many student and community service activities. After this hard work, I was lucky enough to receive one of the most difficult scholarships from the U.S. embassy in Cairo and the Department of State. My dream came true and I finally traveled to my dream land, or as I thought at this time.

When I was in the USA I studied for a few short weeks with the Dialogue Institute at Temple University, but it was a turning point in my life. I studied religious pluralism, diversity of cultures, and policy, and learned more about American society close up. I studied Islam from a Western perspective, Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism, and Hinduism. I discovered new religions that I have never heard about before - like the Quakers - and I lived with them in the heart of the Philadelphia forest to study more about them and their leader William Penn, and how they made a significant impact in the foundation of the principles of the American constitution and the American policy.

This heavy experience shifted me from a closed-minded person to a person who is always eager to learn about themself, not only from the difficult experiences of life, but also from others, and let me accept not only different ideas than mine but also the ideas that are completely against mine.

Now I believe in humanity and believe that everyone in this life has their own journey in which they wake up to themself, then to their shadow, and then to their potential. I have to respect every human being on the earth - as life is not a straight path - it is a trial and error and trying different things by figuring yourself out who you are and who you are not.

And finally, I accept the fact that I can change the world by changing myself, and by being kind to myself and everyone.

This blog post was written by a Study of the U.S. Institutes (SUSI) Alumni - a program that the Dialogue Institute implements in partnership with Meridian International and the United States State Department. To find out more about the SUSI program, click here.

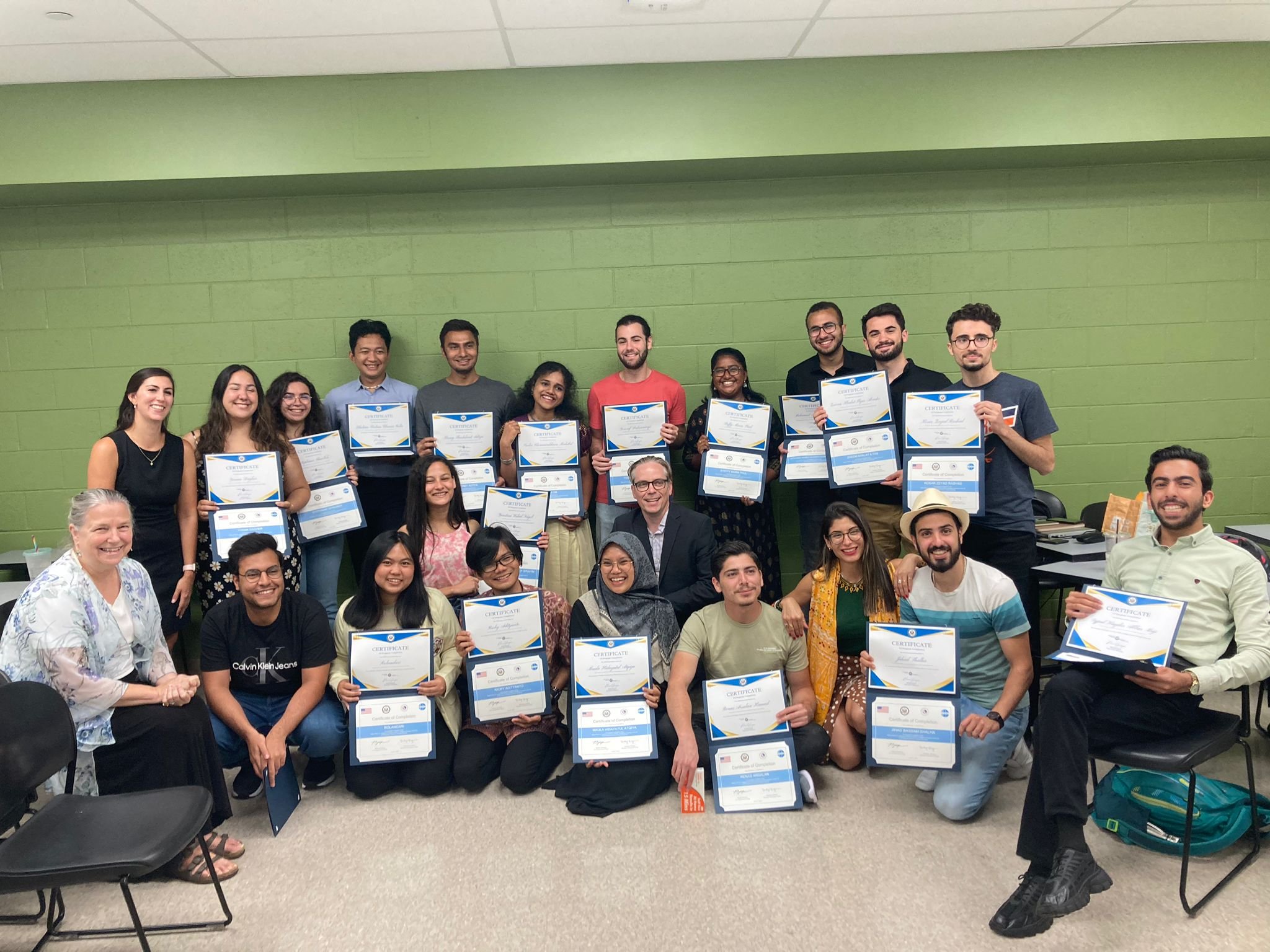

SUSI Summer 2022 Religious Freedom and Pluralism in the United States

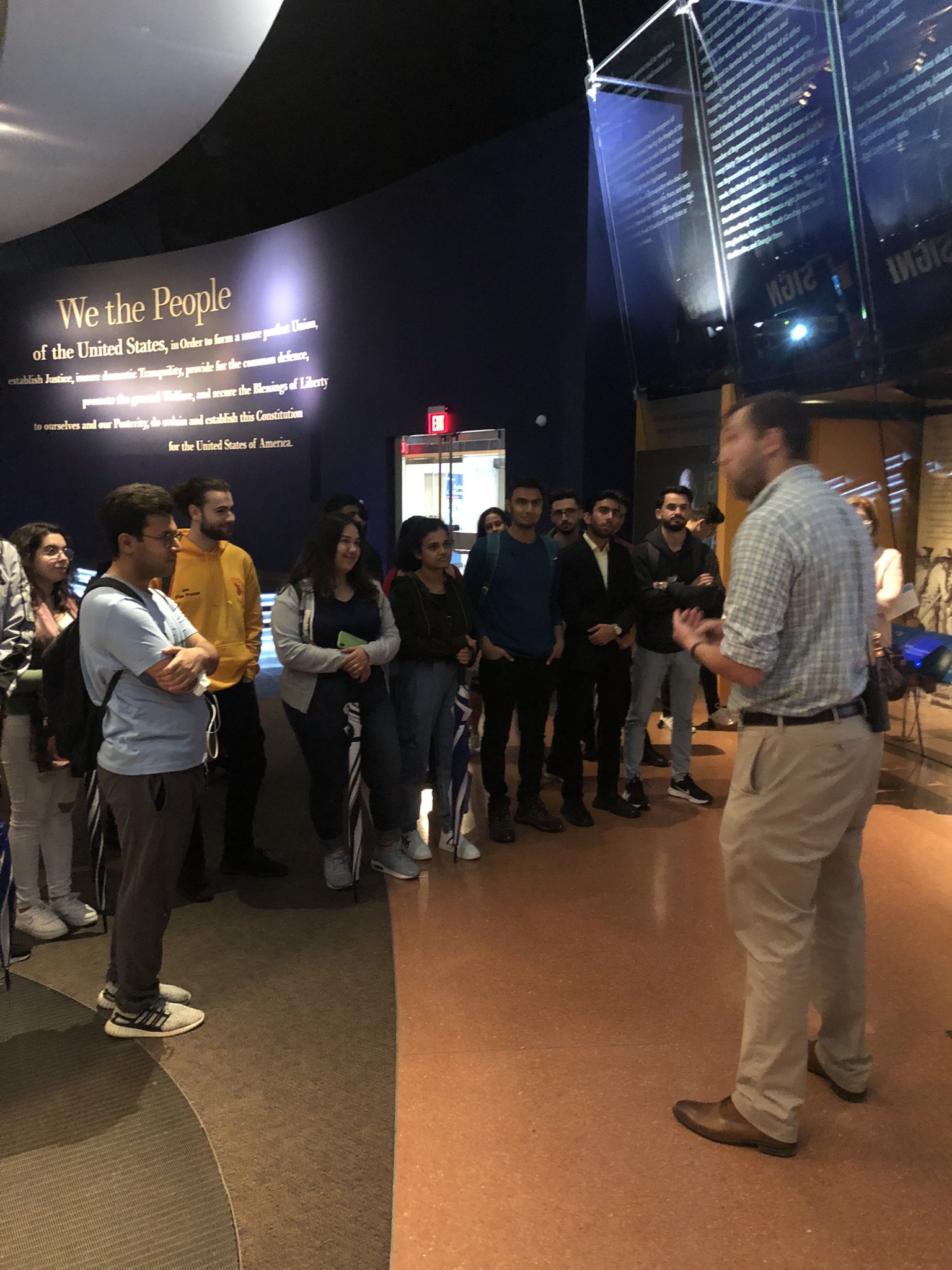

This summer the Dialogue Institute hosted 18 students from Iraq, India, Indonesia, Egypt, and Lebanon for another SUSI Religious Freedom program.

Students engaged in workshops, lectures, and team-building exercises, and were able to explore the city of Philadelphia and the mid-Atlantic region for 4.5 weeks.

Participants learned about issues of diversity, pluralism, and American culture in the Philadelphia area as well as in the greater United States. They learned from religious practitioners, law professionals, academics, civil servants, and community members throughout their visit. Our participants were able to visit Washington, D.C., Virginia, and Lancaster, PA in addition to their Philadelphia stay.

Some highlights of their program included a visit to the Amish in Lancaster, PA, celebrating Eid at the ADAMS center with DI board member Abdullah Antepli, meeting the Abrahamic house fellows in Washington, D.C., and being able to explore Philadelphia in the busy summertime. We were lucky enough to have several DI board and community members with us this summer to mentor, teach, and dialogue with our students. The DI gives a special thanks to Majid Alsayegh, Gity Banan- Etemad, Kay Yu, Nancy Krody, Dr. Rev. Mark Tyler, Abdullah Antepli, Rebecca Mays, and Sean Chambers who supported our students and made this year such a success. We also appreciate all of our volunteers and SUSI staff for all of their hard work.

Our SUSI program closed with the students presenting their community action plans which they created during their programing. Participant community action projects ranged from integrating pluralism in their home universities to hosting workshops for their own NGOs back home. It was clear our 2022 cohort learned a lot from their SUSI experience and while we were sad to see them go back home, we are excited to see all they will do in their home communities.

Malahat Veliyeva: A Dialogue Institute Interview

Malahat Veliyeva is an alumna of the Dialogue Institute’s 2019 Study of the U.S. Institutes for Scholars program. She is an Associate Professor in the Department of English Lexicology and Stylistics at the Azerbaijan University of Languages where she teaches American studies and multiculturalism. Professor Veliyeva was interviewed by Ivanessa Arostegui, a Temple University student pursuing a PhD in religious studies.

Ivanessa Arostegui: Good evening Malahat. It's evening, where you're at, and we are so, so happy that you're going to be able to spend some time with us and talk about how Islam has impacted your life and how you see it within Azerbaijan, going to talk to us about a very specific holiday, and we really appreciate your time here with us this morning. So I want to begin by having you introduce yourself.

Malahat Veliyeva: Thank you very much. I'm also delighted to talk to you this evening, it is evening in Baku good morning to you in Philadelphia, I am Malahat Veliyeva I teach American studies and multiculturalism at Azerbaijan University of Languages, I am a SUSI scholar, 2019. And I had a wonderful experience at Temple University, specifically at the Dialogue Institute with our colleagues with Len Swidler, David Krueger, and Rebecca Mays. These are wonderful people who made our SUSI journey very interesting and useful for us and more informative, educative for us.

Ivanessa Arostegui: Great. Thank you so much for introducing yourself and explaining your connection to the Dialogue Institute. We're so happy that you had a great experience here. It's probably a very different city than where you live, and you know, I'm glad that you were able to make so many connections and, hopefully, you still feel connected to the Institute and we're so happy that you're able to be here with us today.

Malahat Veliyeva: Yes, I am yes, thank you very much for the question. And I'm still connected with our colleagues at the Dialogue Institute now via email. We contact with each other, we send articles to the Journal of Ecumenical Studies, and at the same time we exchange our views on different events happening in the world, we still keep in touch with each other and also, I would like to mention very valuable ideas very valuable experience that I bought about religious pluralism and studies of American society. When I was a SUSI scholar at Temple University, we visited different states, we visited Arizona, we visited the Grand Canyon. So it was an unforgettable experience actually.

Ivanessa Arostegui: Yeah it sounds amazing because you were able to meet all these people, but also see the United States and have these very unique experiences and all of these different sites, you know historical sites and sacred sites and I'm sure that that really kind of gave you a well-rounded understanding it's- it's one thing to meet people it's another thing to go physically and see places experience and walk and yeah so wonderful Okay, so you are Muslim correct.

Malahat Veliyeva: Yes, I am.

Ivanessa Arostegui: Okay, so now we're going to transition and talk about Islam and your experience with your religion, so my first question is just how does Islam affect the way that you see the universe, or the world or other people like your perspective and your lens like how does that focus things in for you in your life.

Malahat Veliyeva: Thank you very much. Islam actually has shaped my views on the universe our planet and other people, since I realized the essence of this religion. I understand that the whole universe, including all living beings, are created by God. Everyone has a mission in this world, some people understand it, some people don't that's why we have positive and negative people, so in my understanding. And this life is a trial for everyone, according to Islam it's an examination, whether we pass or do not pass this examination will be known in the other world when we change the way we exist. You know people work they do their best to achieve something to make fortune sometimes to get some financial benefits, but when we return to God, we will not be asked how much we have accumulated how much fortune we have made, we will be asked how much we give away, so this is the essence of life, this is my philosophy of life, according to Islam.

Ivanessa Arostegui: That's beautiful yeah so it affects everything your whole complete understanding of everything in the universe and you're like you said mission, while you're here while you're alive, which is it sounds like rooted in generosity and kindness and compassion and giving right because, for you everything in the physical material world is nothing really. When we return back to God.

Malahat Veliyeva: Yes, we will all return back to God and we should all realize it and whatever surrounds us our life, the planet, universe, people, all these things are you know given for us like examination. Like trial for us in this world. So that to give a kind of report in another world about our actions about our deeds like this.

Ivanessa Arostegui: Yeah perfect, so I guess, we can segway into actions and deeds behaviors, how do you feel Islam kind of shapes the way that you make decisions in your life or how you interact with others.

Malahat Veliyeva: It has enormous impact on my life my actions, my behaviors are determined by my religious views. Also, my personality. I am a woman and a woman in Islam, should be educated in order to educate her children the future generation to educate others. A woman is not only in miserable creature deprived of her human rights under hijab as in some Muslim countries, women are very active citizens in Azerbaijani society, of course, we also have some gender problems. So in faraway regions of Azerbaijan, there are some gender problems.

Infringement of women's rights, etc, but overall in our society, women are very independent. They're everywhere they're in politics, they're in education and spheres of education, they are in business. Everywhere, and so women in our society, women should be educated everyone - everyone tries to educate, especially girls in the families, because. In the future, they might face a lot of problems, a lot of difficulties like social problems, divorce or any other problems, so that if they have a good education they might somehow support themselves support their family so.

Ivanessa Arostegui: That's wonderful yeah, I mean I think that's sometimes people have a lot of negative associations or stereotypes or ideas of other religions or other places that they're ignorant of, and unfortunately they just fill in you know the gaps or the ignorance and their knowledge by something they saw one time or an idea that they might have by somebody else that doesn't know anything about this country or this religion. But I am glad that you mentioned that it's a complicated spectrum in terms of the situation for women, but from your experience and in the cities that you grew up in and that you lived in you saw a type of Islam, where women are you know, prized within their society, as you know, very important to the family and Islam in general I think also encourages so much the search for knowledge, and so, women are also a part of that and becoming educated. And it wouldn't be fair to have that negative stereotype that sometimes comes in.

Malahat Veliyeva: Education, women's education is great priority in our society, and everyone strives for that everyone tries to give education to their daughters, especially in families with daughters, you know because I think education, Dostoevsky said that beauty will save the world, but I think education will save the world, you know, because even Islam, even to the studies of Islam, we should approach it from the point of view of you know, education. If we study Islam as it is, if we study real Islam if we investigate Qur’an we will see that it is, it is quite you know- more than religion, and there are a lot of answers to our questions there, we can find, although it was written many, many centuries ago, yeah.

Ivanessa Arostegui: Yeah, great so then my other question in relation to Islam is about religious practices that you feel might bring the community together or might build bridges of connection or communication. I don't know if you want to share some of those practices with us today.

Malahat Veliyeva: So religious practice, for example in Azerbaijan, there are two contrasting Muslim directions like Shi’ism and Sunnism and they successfully coexist in Azerbaijan and even they complete each other, like there is a tradition every Friday both Shi’is and Sunnis, they come to the mosque, and they pray together and after praying they just shake their hands greet each other, and they are very friendly with each other, you know. But what can we see in in Middle Eastern countries in other countries, so where Shi’ism and Sunnism are confronting with each other, and they are competing for leadership in Islam and so these things are. I think beyond our understanding. So these are two directions in Islam, and they should coexist together and we are all people we are all equal in front of God we are the same for God, you know, yeah and people should understand it, these religious practices. Then we have Ramadan and during the month of Ramadan. So it is fasting you know Muslims all over the world, they do fasting, and they eat at the same time, they just do the same rituals and it's somehow you know unites people all over the world, especially the Muslims all over the world. They understand what do the poor people experience what do hungry people experience and they try to be more merciful. Ramadan teaches people to understand each other to be more you know sympathetic to each other yeah and I think this this tradition, this religious practice should continue and the people, especially the Muslims all over the world, they should preserve these traditions and practices.

Ivanessa Arostegui: Yeah yeah it sounds like you believe that these practices connect - like you said, not just local Muslims or Muslims within one country but it's a whole global community of Muslims of brothers and sisters in the whole world that can come together with these practices. And that can help them connect to everyone, like you said, even people that might not be in that similar situation if they were blessed monetarily or with certain blessings within their family, they also have time to contemplate and to think of those that have less than they do. So that you really think that this is something that connects Islam, not just to the Islamic community, the global Islamic community, but to humanity to all humans and the suffering of everyone. Alright perfect so now we're going to get to a particular holiday that you're going to talk to us about so which holiday, are you going to talk to us about.

Malahat Veliyeva: I would like to talk about Eid Al Adha, it is called Gurban holiday, feast of sacrifice, yes, it is one of the grandiose holidays in the Islamic world and, as most of the important surmises of Islam Gurban, Eid Al Adha is demanded by Qur’an.This holiday is a part of Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca and the holiday of sacrifice is usually celebrated on the 10th day of the 12th month of the Muslim calendar Dhū al-Ḥijjah and this holiday, it is also a good practice for uniting Muslims all over the world, it is peculiar only to Islam. So I would like to talk a little bit about the history of this holiday it's related to the Prophet Abraham who brought his son as a sacrifice to God he wanted to kill his son as a sacrifice to God and at this moment he saw he got a message from God to cut the sheep. To cut the ship, and here we can see Islam how Islam prohibits any kind of human sacrifice how human life is valuable is important in this world, especially for God and God here recommends him to sacrifice the animal, instead of human, instead of his son. To give the holiday more respect it was determined to celebrate it once on the 10th day of Dhū al-Ḥijjah, as I said, and I would like to say some quotation from Qur’an from the Surah 5 Ayat 97: “Allah determined Bayt al-Haram, sacred house, Kabb’ah, the sacred month, tied and untied neck with and without signs on their necks, sacrifices brought to Kabb’ah to be a way to put into order the lives, religious and world affairs of the people.” It is the quotation from Qur’an about Eid Al Adha, and it is possible to bring the sacrifice for the realization of some wish and so we have different kinds of religious ceremonies. But the most important ceremony, the most essential one is cutting sheep and giving away to the poor to the needy families to hungry people and see the most interesting thing about this holiday the unique fact about this holiday is that prophet Abraham brought his son to kill as a sacrifice to Allah but Allah offered him to cut the sheep and it is, it is you know very, how to say, important message from Allah to people - so don't kill yourselves don't kill each other, because human life is very important. You know, and when people cut the sheep and give out meat and give it like gifts like mutton, it teaches people to understand that they should be helpful to each other, they should help each other in difficult situations and also if the Muslim knows that his neighbor or his relative or someone else's hungry and he shouldn't be indifferent to this, he should support them, he should help, and so this holiday this day, Eid Al Adha is like you know attribute of Muslim unity not only Muslims, so we cut sheep and we give away even to people who are not Muslims who were just people from other religions, like Christianity Jewish etc yeah. And I think it is - being merciful, being generous is very important.

Ivanessa Arostegui: Yes, great, so that is very beautiful, I grew up practicing Christianity and there's no form of animal sacrifice there's sometimes in Christianity forms of like self-sacrifice where you sacrifice maybe something that might be very dear to you let's say maybe during a particular time period, and we do something that for yourself is kind of painful like maybe you don't use your computer or your technology and that's going to hurt you a little bit because you're so used to going on your computer using your phone and so forms of self-sacrifice there isn't forms of animal sacrifice really in Christianity, but this is, this is a very unique practice in Islam and like you said ties very specifically back to Abraham who is so important within Islam and within all of the Abrahamic traditions. Is this holiday, or is this practice, do you feel that in any way it brings together a larger history for Muslims, for them to like connect with the larger history of who they are in some way, do you feel it plays that role or?

Malahat Veliyeva: You know, yes it comes from history and at the same time, Muslims all over the world, they try to. To preserve this history and to connect it with modern life to connect it with modernity, because many years have passed, many centuries have passed since Islam has been established on this planet, on our planet. So it makes you know people, especially Muslims, how to say, merciful and grateful to God.

Ivanessa Arostegui: Beautiful. Okay, and our last question about this holiday. How do you feel about practicing this particular holiday, or being a part of the Feast of the sacrifice for you or from some around the world, how do you feel that that connects Muslims to God.

Malahat Veliyeva: This story passes from generation to generation, and it is told in mosques, it is spreading on social networking sites as well. For the young generation to be well informed about it, and every year we celebrate the holiday as remembrance, to the prophet of Abraham and his son Ishmael who was saved by God let's say who was you know given us a gift to his father again like this yeah and I think it's our duty to preserve this holiday and to celebrate it every year and to pass this information from generation to generation- so our holy book Qur’an exists, and I hope it will exist forever. For future generations for humanity to learn how to live to understand the philosophy of life to understand how to become a good human, a real human being.

Ivanessa Arostegui: Yes, so important right to have these holidays, these rituals that connect to a really long line of people and ancestors that have experienced the power of God and to continue to walk in faith and to continue to preserve that history, that has been there for so long and to allow it to effect now, right the present, how you said how we decide to live with others, and what we decide to highlight and prioritize and so very beautiful, thank you so much, we really, really appreciate your time with us this morning.

Advocating for Child Protection: Maria Emad

By Maria Emad

Egypt, SUSI Cohort 2018

In an era where internet plays a vital role in shaping people’s wildest imaginings as well as replacing genuine knowledge with “the wisdom of the crowd” dangerously blurring the lines between fact and opinion.

In an era where there are always multiple ways for everyone to express themselves, many are heard yet still feels not heard, and especially children, the most vulnerable citizens in our societies.

Children don’t have enough understanding and cannot be aware enough to sort out or advocate against abuse, violation of rights, and distorted social norms. For, as Chief Dan George states, “a child does not question the wrongs of grown-ups, he suffers them” .

Likewise, Susan Forward notes, “a child that’s being abused by its parents doesn’t stop loving its parents, it stops loving itself”. Susan’s words draw attention to the concept of “loving” and contemplating the way humans perceive and convey such repetitive word in daily life.

And what I mean by love here is not the love of the romantic world and theatre. A love mixed by beauty and charm and sensuality taken down in shorthand is just robbed of its higher purpose which is cherishing and nourishing. Love is supposed to be primarily fulfilled in childhood, with all forms of emotional security, unconditional love, and empathy with the child’s feelings. Children also require respect for their developmental level, sensitivity to the child’s needs, and verbal and physical affection. All of us develop our core identity, our expectations about how people will treat us and about our perception of loving based on our relationships with our parents.

“Children of toxic parents grow up feeling tremendous confusion about what love means and how it’s supposed to feel. Their parents/ caregivers did extremely unloving things to them in the name of love. They came to understand love as something chaotic, dramatic, confusing, and often painful—something they had to give up their own dreams and desires for.” Susan Forward with Craig Buck., 1989. Toxic Parents. New York: Bantam Books.

That requires from us, as Child Protection Activists, to try to put ourselves in the place of a child, and to see what it means for a child to feel loved and protected. Activists also work to ensure children are in an environment that creates a sense of being valued, and cherished, and enjoying safety, knowing that, if something goes wrong and if there is a risk or a fear, someone is ready to intervene early enough for the fear not to grow.

The negative disparity of childhood experiences and the impact of our cultures that pass down from one generation to another, result in adults who suffer from mental illness and a lack of connection to their values [21]. These scars are passed down from generation to generation forming engrafted patterns that we never wish for, as the link between experiencing violence, neglect, exploitation or abuse in childhood and the lifelong impact of these results in adults are plentiful.

The early moments of life offer an unparalleled opportunity to build the brains of the children who will build the future. But far too often, the opportunity is squandered when patterns of violence and emotional abuse are interchanged with reconciliation and nurturing. This zigzag can be especially damaging for children who only experience cycles of abuse-reconciliation-nurturing followed up by abuse again as they grow up. Unfortunately, as these children mature then they often repeat these patterns in their own intimate relationships and families.

The science is clear: a child’s brain is built, not born. While genes provide the blueprint for the brain, a child’s environment shapes brain development.

Millions of the world's most disadvantaged children are deprived of the opportunity to be fully developed, Children living outside a family environment are especially marginalized: Children living in detention facilities, orphanages, on the street or in refugee camps require additional protection, resources, and support to ensure their rights are not being denied.

Children that are in greater risk to get exposed to sexual exploitation, child trafficking child labor, children without parental care, children associated with armed forces and groups, and children who grew in communities that do harmful traditional practices such as social norms like female genital mutilation and child marriages.

Prevailing norms can determine whether violence – among children and adults – becomes the accepted or even expected response in cases of small disputes, perceived slights or insults. So, it’s not surprising that in compulsive cultures and marginalized communities where the culture of dialogue and communicating issues do not exist that they reconcile with such norms. People also have little information about child development, so they follow their instincts or their own childhood experience. But, many times, such instincts are emotional reactions that aren’t well through-out. And sometimes their childhood experiences were negative, or even violent ones. Sometimes parents think that violence is the only mean to discipline children. They fear to lose control, so they resort to short-term approaches which cause long-term distortions. Violence can make a child stop doing a certain act out of fear and fright of adults’ anger/reaction and not out of actual behavioral change. True changes in behavior needs communication and dialogue. It needs efforts, patience, the willingness to understand one another as a human being, and acknowledging their needs.

Violence, according to the CRCE, includes all forms of physical or mental violence, injury and abuse, neglect, or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse. So, a very comprehensive and extensive range of different forms of harm, from physical and mental violence, to maltreatment or exploitation, to negligence (also including the detention of children because of their or their parents’ migration status)

Emotional or psychological violence and witnessing violence includes restricting a child’s movements, denigration, ridicule, threats and intimidation, discrimination, rejection and other non-physical forms of hostile treatment. Witnessing violence can involve forcing a child to observe an act of violence, or the incidental witnessing of violence between two or more other persons. Source: INSPIRE: seven strategies for ending violence against children (WHO, 2016)

An estimated one billion children, half of all the world’s children, experience violence every year. [1, 2]

Adding to the aforementioned statistics, violence affects children across class, ethnic, educational, and religious groups. This is not just a problem of the very poor. It's not just a problem of particular religious groups. It affects all children, rich children, privileged children, children from educated families.

“According to statistics gathered in 2002, over 150 million girls and 73 million boys had forced sexual intercourse or sexual violence imposed on them. And this data doesn't even cover trafficking of children or labor exploitation, nor does it cover a probably much greater hidden body of violence, violence that's hidden because children are fearful about reporting it, or violence that's hidden because it's socially accepted, maybe by the children themselves, or violence that is hidden because there are no trusted outlets for children to reveal the secret. There's no trusted person. There's no one they're encouraged to go and speak to report the violence.

Moreover, between 22 per cent and 84 per cent of children 2–14 years old experienced physical punishment in the home in 37 countries surveyed between 2005 and 2007.”

In light of this finding, we can talk about Child Protection and its ways of implementation. Child protection is really about having those systems that safeguard our children from exploitation, from violence, from abuse, fear, and even neglect, making sure children grow in a very healthy environment that nurtures their holistic growth. Child protection should foster a healthy, enabling, and supportive environment to ensure a child's well-being and ability to live free of violence and realize their full potential at home, school, or the community in general.

Realizing children’s rights to a violence-free childhood Actions to end violence in childhood should be seen as part of a “rights revolution” which has extended the rule of law to cover violence within the most private of places – the home. The CRC encapsulates such aspirations, and recognizes that children are the foundation for sustainable societies. Children are not objects, but persons with rights of their own that must be articulated and enforced. Children can pursue many aspects of these rights themselves. Indeed, they often have a strong sense of fairness and justice. Nevertheless, children often have no voice to express the traumatic effects of violence, and have little capacity to influence public decision-making. Children rely on responsible adults and on society to intervene on their behalf for their safety and well-being.

Prevention is possible. “The launch of the Global Partnership to End Violence against Children in 2016, serves as a global platform whose aim is “ending violence against children in every country, every community and every family” (End Violence Against Children, 2018)”.

Essential public action should be taken, not just by governments but also by civil society, international organizations, academia, researchers and the media.

All people should unite to end violence in childhood – to break the culture of silence, strengthen violence prevention systems, and improve knowledge and evidence.

We all must get in the ring and break the silence. The first task is to break the silence around childhood violence. Violence needs to be spoken about and made fully visible. Traditional and social media can highlight the scale of the problem and help change attitudes and behaviour. They can challenge gender and social norms that belittle the dignity and freedoms of women and children, while also highlighting the extent of violence against boys, and against children who are vulnerable because of sexual orientation, disability or ethnicity.

Leaders, governments and communities across the world are in a position to transform children’s lives and the futures of their societies, establishing the basis for a just, peaceful and equitable world – a world worthy of its children.

Approaches to prevention cluster into three areas:

1- Those that enhance individual capacities

2- Those that embed violence-prevention strategies into existing services and institutions

3- Those that eliminate the root causes of violence

Enhance individual capacities: Well-informed parents and caregivers can both prevent violence and create a nurturing environment free from fear in which children can realize their full potential. Children themselves can also be equipped with skills that build resilience and capabilities.

Embed violence-prevention in institutions and services: Violence is interwoven into the everyday lives of children and women. Prevention should correspondingly be built into all institutions and services that address children’s everyday needs.

Eliminate the root causes of violence: Societies and governments should work with families and communities to address many of the root causes of violence – to establish violence-free communities and change adverse social norms.

Once archaic doctrines of original sin are discarded, we can see the clear evidence that the roots of serious criminality in children develop and flourish from adult – mostly parental - violence and neglect, compounded usually by a failure of the State to fulfil its obligations to support parents in their childrearing responsibilities and to provide children with absorbing and rights-respecting education. The more serious and extreme a child’s offending is, the more certain we can be of its origins in adult maltreatment – or sometimes simply the tragic loss of parents or other key carers.

The child lives in the family. The family is affected by the community. And of course, the community is surrounded by state institutions, civil society, and international organizations. We need a preparation system and ongoing training and support and supervision and a higher education system that has the capacity to train not only child protection workers, but those that are working in health and teacher preparation, so they can be responsive to child protection issues.

SUSI Podcast Episode #1: Irine Kurdadze

Welcome to a special podcast series from the Dialogue Institute/Journal of Ecumenical Studies. The Journal of Ecumenical Studies or (J.E.S.) was founded by Temple University professors Arlene and Leonard Swidler in 1964 as the first peer-reviewed academic journal in the field of ecumenical and interreligious dialogue. In 1978, Professor Swidler hosted the first of a series of conferences which brought together leading scholars from each of the Abrahamic faiths in regions where interreligious understanding was crucial to promoting stability and peace. In 2008, these and other efforts gave birth to the Dialogue Institute, which applies the cutting-edge research of the journal to grassroots efforts to facilitate dialogue and understanding across religious differences.

The DI-JES is based at Temple University in Philadelphia. This series of interviews features participants from our Study of the U.S. Institutes, or SUSI, Program on Religious Pluralism and Freedom, which was funded by the U.S. Department of State. From 2017 to 2019, the Dialogue Institute hosted three cohorts of scholars from dozens of countries and you’ll get to meet several of them in this podcast series.

Introducing Dr. Irine Kurdadze

This first interview features Professor Dr. Irine Kurdadze, who is the director of the International Law Institute at Tblisi State University in the country of Georgia, a country at the crossroads of Asia and eastern Europe. She is a professor of International Law whose research and teaching focuses on academic and specific practical student-oriented activities. In addition, she has served as a Member of the Georgian Parliament and was a Deputy Chair for the Foreign Relations Committee, joining a member of the Parliamentary Delegation to the Council of Europe. Her passion as well as her intellectual integrity and acumen correlate international law with domestic law according to rigorous global standards.

My name is Dave Krueger and I’m the executive director for the Dialogue Institute. For this episode, I’m joined by Rebecca Mays, our director of education. Rebecca and I had the privilege of meeting Dr. Kurdadze in the summer of 2017. In this interview, Irine discusses how the SUSI Scholar program affected her and served as a catalyst for a new university course that teaches international standards of ethics and religious minority rights. She sees the course as vital to the health of diverse societies.

Rebecca and I spoke with Professor Kurdadze while she was in her office in Tiblisi, and in the background, you will hear the lively street sounds of her city. Without further delay, we turn to our conversation with Irine Kurdadze.

Interview Transcript

Rebecca Mays: As someone who can blend one's own personal character with one's own professional responsibilities, I’m curious if there were one or two formative experiences in your life that would, one, account for your ability to blend integrity and professionalism and, two, explain why you chose this work.

Georgia is located at the crossroads of Eastern Europe and Asia.

Irine Kurdadze: Thank you, first of all, for giving me this opportunity to join this wonderful project. You know, why I started to work on minority issues is related to the experience I gained as both an international lawyer and as a person involved in the public sector. I wanted to combine my theoretical knowledge of international public law and the practical challenges faced within the 17 public offices in the Ministry of Education. In the Ministry of Education, one of my job responsibilities was to support the integration of ethnic, religious, and linguistic minorities into Georgian society. And as you know, Georgia’s multinational, multi-religious states mean that ethnic and religious groups are living in the common space of this small country. One challenge that I saw was that the settlement of minority issues had been challenged by the giant system of the state institutions. In addition, the dominant population lacked knowledge of minority issues. To my thinking, one solution to the problem was to provide as much possible information about all the groups living here in our country. By increasing the level of knowledge and thus the level of tolerance, Georgia’s Parliament was able to adopt a couple of national strategies to help the civic integration of religious and ethnic minorities. These strategies were intended to raise awareness about the rights of minorities with an aim to eliminate all forms of discrimination and to promote the engagement of minorities in the social life of our country. I truly believe this goal can be reached and reaching it is why I entered this work. Through increased knowledge of the relevant fields as well as analyzing international standards and domestic jurisprudence, I can both elaborate the syllabi I teach and empower professionals in public service. I want to help students and professionals with the knowledge that will help them to cope with existing challenges that we unfortunately still have.

Rebecca Mays: Thank you, Irine. Your university and country should be glad you made these choices.

David Krueger: We had the privilege of spending the summer with you in 2017 when you were a participant in the SUSI scholar program here in Philadelphia. Could you share a little bit about how that summer experience impacted you?

Irine Kurdadze: First, thanks to the embassy of the United States here in Georgia and to the State Department, I was privileged to participate in the SUSI exchange program in 2017. This was not my first experience of traveling to the United States being a public servant. I have been several times and I have been privileged to participate in different high level meetings or study visits. These visits, undoubtedly, were an important and valuable experience for me on a personal level as well as on an institutional level. I always try to follow the current political or social processes in the United States with great interest. As a consequence, I had a feeling that I would understand well the important roots of the United States public life.

Despite such diverse experiences of other trips to the U.S., participating in the SUSI program gave me a different perspective on both the individual and academic social levels. I knew the program would be useful for my current career development, but, in reality, the program content and design exceeded all my expectations.

It is not surprising given that the bulk of the program itself is very multi-disciplinary and takes place in a very historical, multicultural city of Philadelphia. It's a great example of how many different cultures and religious communities as well as immigrant newcomers could coexist in one place, united by the American spirit of seeking equal opportunities. To my thinking, the goodness of this program represents a unique opportunity to experience a special type of knowledge acquisition that pushes beyond the capabilities represented in scientific papers. The SUSI program was designed in a way that allowed us to create our own impressions and generate our own conclusions about the laws and policies of the United States regarding religious and cultural diversity.

Second, meeting with local religious communities made an incredible impression on me. No matter which group we met, the people were ready, not only to present the best experience possible, but were also happy to meet us as representatives of foreign countries, often a country about which in some cases, they did not have much information. They were ready to share experiences about challenges which they sometimes face and discuss their own vision of solutions.

Third, no less valuable for me was the interaction with the SUSI Scholar program participants themselves. My fellow cohort members taught me so much about what is going on in other countries. I was able to learn so much from people with different visions and attitudes.

Also I would like to focus on the role of the host institution and its capacity. I want to thank the Dialogue Institute and its whole staff. All of you were supportive, ready to provide any assistance to the needs of the participants. I am really happy to say that I gained friends and colleagues from the Dialogue Institute in addition to the program experience. In fact, they and the program inspired me to handle different kinds of activities here in my country at my university.

David Krueger: Irine, could you share some about the work you have been doing at your university in Tbilisi and also what you will be doing with the mini grant you recently received from the State Department?

Irine Kurdadze: For one week in the spring of 2018, I offered to my students a course focusing on international standards of ethical and religious minorities’ rights. We were discussing what it means to be diverse, to be a multinational country. The purpose of this event was to foster dialogue between majority and minority ethnic and religious student representatives. Another activity I offered was with the support of my university and my colleagues. I offered study visits for MA students who are enrolled in my classes to meet local ethnic and religious community representatives. Unfortunately recently due to Coronavirus, we cannot manage to organize the same activities, but I do hope that we will do so next year. This project focused on multinational equality aims at the serious interest of the students who want to deepen their knowledge in the protection of rights of national religious minorities. The project also involves students in research using an interdisciplinary teaching methodology. We went to the region where most of the religious and ethnic minority groups are living, which gave us the best opportunity to meet with most of these groups.

Also to my thinking, this project included raising awareness and achieving many educational components. First, students recognize the need to be in the local communities. Secondly, they prepare a research essay related to the minority rights and finally, such events stimulate open discussion on minority-related subjects in larger public interests groups, even in the international law system. But still, the most important components are at the domestic level. Understanding the local domestic issues will be important for us to be able to face the kind of challenges we do face here in our country.

The mini-grant helps to promote more opportunities of creating space for dialogue among the youth because in a couple of years they will be decision makers for our country. And I think that they have to have a clear and deep understanding about democracy and the demographic situation about the groups who are living here in our country. They will need a clear understanding of what it means to be a multinational country. What does it mean to promote toleration? The award will help foster non discrimination enlightenment and discussion about what can be done now and in the future.

Rebecca Mays: We are grateful that you took so seriously your study and experience in the US and care about the education of these youth. We want to make a transition now to the larger scene of the globe and of America. In particular, we Americans are at a time when we need to learn more about some of these purposes in your courses. What aspect or example of international law pertaining to religious freedom do you think we Americans should learn more about?

Irine Kurdadze: You know, it's a very interesting question. And, of course I respect the best experts in the United States legislation, but I will try to share my opinion. Generally speaking, international human rights law provides an important framework for the rights of all people in all countries. At the same time international law provides minimum standards that should be fulfilled by the member states. In different countries, these minimum standards are different depending on the legislative system and on how best to implement international laws within domestic law.

Generally speaking, these domestic standards do not become enforceable unless and until they are implemented through the federal law. It's very important to know and understand how international law is working in the domestic space in each country. International treaties define rights very generally and international courts can provide monitoring. But the ability to enforce a decision directly in many countries, including the United States lies with the federal government within each country. One of the best ways to improve international human rights is to legislate and to track legal protection mechanisms for human rights with the support of judicial systems within each country.

I just want to add that the United States has been an active supporter of a strong system of human rights protection. Many of us as lawyers read on the State Department platform the special reports on particular countries they produce each year as a resource to our teaching and practice. Besides that, the United States was one of the leaders in creating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. And the United States is nowadays a member of many international treaties, despite it still not being fully committed to all of these human rights treaties, of course.

One of the mechanisms I love to present to my students is a Universal Periodic Review system known as UPR. The United States does participate in this mechanism. All interested organizations and institutions that are operating in the United States have the opportunity to apply, using the State Department's platform, in order to obtain information about particular situations in a given country and conduct. I presume the United States government also conducts consultation with civil society and academic representatives during the preparation of these reports. Also the Department of State provides an email inbox for persons in academic or civil society work or even the general public to send questions and voice their concerns. It is a great opportunity.

Rebecca Mays: Very helpful. Thank you.

David Krueger: In your work in global international law, what do you see as the most pressing concern in your region or beyond?